RELIGION AND THE FOUNDING OF THE AMERICAN REPUBLIC SYMPOSIUM

An Exhibit at the Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building

June 18 - August 29, 1998

The following article resulted from a clipping that was sent to Christian Heritage Ministries for analysis and comment by a concerned Christian. Published in the October, 1998 issue of Focus on the Family Citizen Magazine, it was written by Robert H. Knight, Director of Cultural Studies for the Family Research Council, and Contributing Editor to Citizen Magazine. It is entitled: How Faith Shaped a Nation, A Library of Congress Exhibit on the Christian Roots of American Democracy.

Knight paints a glowing picture of the exhibit's "proof that America's founders were largely Christian..." However, this author took down verbatim, the exhibit's wording upon wall and within glass encasements, together with acquiring a copy of the Chief of the Manuscript Division, James Hutson's glossy handbook description of his own exhibit.

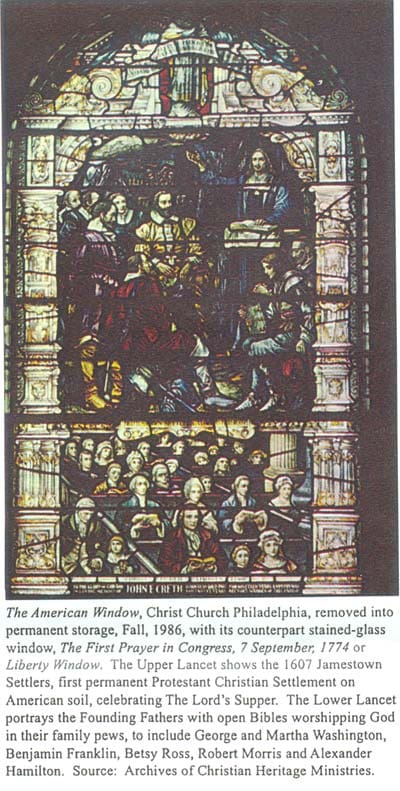

My analysis differs from Mr. Knight's account, in that the Jesuit and Roman Catholic Religion played no part whatever in The Founding of the American Republic, although predominantly featured in the first, and therefore primary, section of the exhibit -- thereby promoting interfaith. The latter never existed at the birth of our American Republic. All of the 36 congressmen depicted in the Christ Church, Philadelphia stained-glass window, "The First Prayer in Congress, 7 September, 1774," were affiliated to mainline Protestant Christian denominations, as were the Founding Fathers of the American Republic.

Upon entering the exhibit, one was greeted with the First Exhibit, hereunder quoted:

"European Persecution. The Religious persecution that drove settlers from Europe to the British North American Colonies sprang from the conviction held by Protestants and Catholics alike, that uniformity of religion must exist in any given society. This conviction rested on the belief that there was one true religion and that it was the duty of the civil authorities to impose it forcibly, if necessary, in the interest of saving the souls of all citizens..."

The Founding Fathers, however, denounced the Roman Catholic Church and popery. This is amply borne out by the organizer of the American Revolution, Samuel Adams' August l, 1776, Independence Hall oration, now housed in the Rare Book Collection of the Library of Congress. In it, he states:

...Our Fore-fathers threw off the yoke of popery in religion, for you is reserved the honor of leveling the popery of politics. They opened the Bible to all, and maintained the capacity of every man to judge for himself in religion. Our glorious Reformers (Protestant)* when they broke through the fetters of superstition, effected more than could be expected from an age so darkened...

The Journals of Congress, meticulously kept by first Secretary of Congress, Charles Thomson, reiterate the Founding Fathers' abject denunciation of Roman Catholicism, while enumerating grievances against the ruling power. The 10th article reads:

10. The late Act of Parliament for establishing the Roman Catholic Religion and the French Laws in that extensive country now called Quebec, is dangerous in an extreme degree to the Protestant Religion and to the civil rights and liberties of all America, and therefore as men and Protestant Christians, we are indispensably obliged to take all proper measures for our security.

The 1620 Pilgrims

Governor William Bradford of the 1620 Pilgrims begins his history Of Plimoth Plantation devoting the first nine chapters to the history of the Christian church prior to their arrival at Cape Cod in November, 1620. As Bradford states, it was essential that he begin with the very root. And that he did. We see this in chapter one, as he discussed the opposition that took place following the Reformation and the downfall of popery:

"It is well knowne unto ye godly and judicious how since ye first breaking out of ye lighte of ye gospel in our Honourable Nation of England (which was ye first of nations whom ye Lord adorned here with, after the grosse darkness of popery which had covered and overspead ye Christian world) what wars and opposissions ever since Satan hath raised, maintained, and continued against the Saints, from time to time, in one sort or other. Sometimes by bloody death and cruel terments; other wiles imprisonments, banishments, and other hard usages; as being loath his kingdom should goe downe, and truth prevaile, and ye churches of God reverte to their anciente puritie and recover their primative order, libertie and bewtie..."

*Parentheses mine

"Persecution of Catholics by Huguenots. In the areas of France they controlled, Huguenots at least matched the harshness of the persecutions of their Catholic opponents. Atrocities A, B and C, depictions that are possibly exaggerated for use as propaganda, are located by the author in St. Macaire, Gasconly. In scene A, a priest is disemboweled..."

The Third Exhibit promoted the Jesuit Roman Catholics. It read:

"Persecution of Jesuits in England. In the image on the left is Brian Cansfield (1580-1643), a Jesuit priest seized while in prayer by English Protestant authorities in Yorkshire. Cansfield was beaten and imprisoned under harsh conditions. He died on August 3, 1643, from the effects of his ordeal..."

The Window Exhibit between the Third and Fourth Exhibits described the Martyrdom of John Rogers, in these terms:

"Martyrdom of John Rogers. The execution in 1555 of John Rogers (1500-1555) is portrayed here in the 9th edition of the famous Protestant martyrology - John Foxe's Book of Martyrs. Rogers was a Catholic priest who converted to protestantism in the 1530's under the influence of Willliam Tyndale and assisted in the publication of Tyndale's English translations of the Bible. Burned alive at Smithfield on February 4, 1555, Rogers became the "first Protestant martyr" executed by England's Catholic Queen Mary. He was charged with heresy, including denial of the real presence of Christ in the sacrament of communion.*" (*The Catholic false doctrine of Transubstantiation.)

Above the plaque depicting John Rogers' execution, however, was the Chief of the Manuscript Division, James Hutson's critique of the famed New England Primer, "as doubtless helping to fuel anti-Catholic prejudice."

"John Rogers Portrayed in New England. Two centuries after John Rogers' execution, his ordeal, with depictions of his wife and ten children added to increase the pathos, became a staple of the New England Primer. The Primer supplemented the pictures of Rogers' immolations with a long, versified speech, said to be the dying martyr's advise to his children, which urged them to "keep always God before your eyes" and to "abhor the arrant whore of Rome, and all her blasphemies." This recommendation, read by generations of young new Englanders, doubtless helped to fuel the anti-Catholic prejudice that flourished in that region well into the 19th century."

Adjacent to Protestant martyr John Rogers' exhibits, was a portrait of Cotton Mather, described as "controversial" and "accused (unfairly) of instigating the Salem Witchcraft Trials." Underneath his description was a facsimile of one of Mather's draft sermons, in tiny calligraphy, framed, but illegible to the public. However, Cotton Mather is depicted under "Theology" in the Library of Congress', 40 Great American Heroes ceiling mosaic, (c.1897) as America's greatest Christian hero.

The 1607 Jamestown Settlers: Hutson's glossy handbook to Religion and the Founding of the American Republic gives the following description of Virginia. Under the heading, America as a Religious Refuge: The Seventeenth Century, we read" "...Even colonies like Virginia that were planned as commercial ventures were led by entrepreneurs who considered themselves 'militant Protestants' and who worked diligently to promote the prosperity of the church."

This is untrue of the 1607 Virginia settlers, however, as borne out by the 1612 and 1626 early Virginia history books in the Rare Book Collection of the Library of Congress; as well as the graphic account of their true identity related in Christ Church, Philadelphia's 1920 Handbook. The latter describes "The American Window," counterpart to "The First Prayer in Congress, 7 September 1774" or "Liberty" stained-glass window (the former not being on exhibit with its counterpart) as follows:

"The American Window depicts the two primary epochs in the history of the Church's influence on the Nation, namely, the first permanent settlement and the attainment of independence. High over all, between two consoles which form part of the renaissance decoration framing the two scenes, stands an angel with outstretched wings, holding a scroll with the words, "Fear not, little flock, for it is your Father's good pleasure to give you the Kingdom." The main subject is The Settlement of Jamestown, 1607.

The little caravel, "The Godspeed," lies at anchor in the river; peering through the stockade is a group of Algonquin Indians; the intrepid Captain John Smith is seated with other leaders of the pioneer band at their daily worship under the ship's sail sheltering them amongst the trees; Chaplain Robert Hunt, "an honest and godly divine," is preaching from the rude board pulpit; the other figures are Captain Christopher Newport, Edward Wingfield, Richard Hackluyt, John Ratcliffe, Bartholomew Gosnold, George Kendall and John Martin, reproduced by the artist from portraits in London. These were the men who, in the providence of God, transplanted the civilization and religion to which we owe our national growth and glory; here, rather than at Plymouth, was the foundation stone of our liberties laid; the Church's prayers offered by devout churchmen consecrated the first deliberative assembly of freemen convened on American soil, kneeling in the primitive church at Jamestown.

With ungrudging appreciation of the contribution of Puritan and Pilgrim and others itheir place and time, it is to be everywhere recognized that the roots of the great vine were bedded first in the warm soil of Virginia, and from thence it hath filled the land. To this, the window bears eloquent witness..."

My conclusion is that the Chief of the Manuscript Division, James Hutson's "Hanging of Absolom" portrayal, chosen for this exhibit's glossy handbook cover, is a more appropriate depiction of the actual contents of Religion and the Founding of the American Republic. This exhibit was certainly not a reflection of "The First Prayer in Congress, 7 September 1774," depicting 36 Protestant Christian Founders of the American Republic in fervent prayer to Almighty God for His guidance in establishing a unique new nation founded under God.

- Catherine Millard